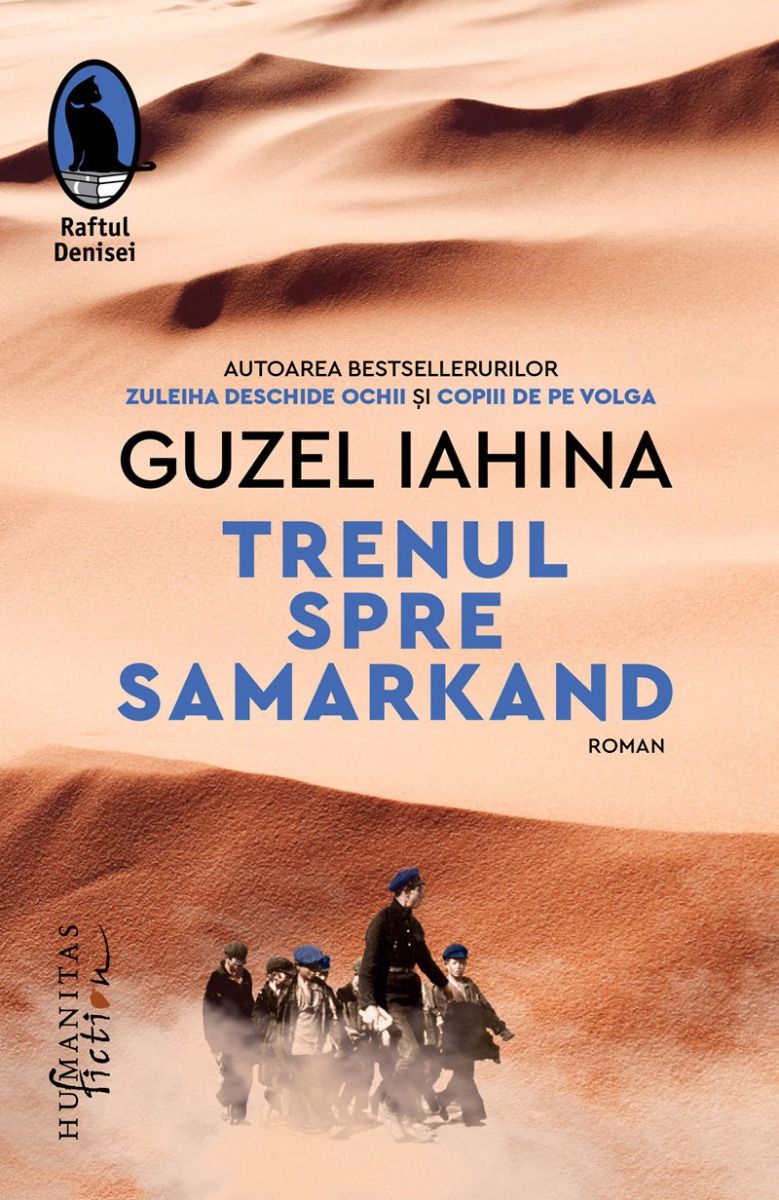

MY REVIEW OF A NEW CLASSIC

Train to Samarkand

Elena Kostiukovici said that books like The Train to Samarkand are rare gems which have the power to change everyone who reads them.

I will try to explain in 5 minutes why I firmly think that is true.

“Books like The Train to Samarkand are rare gems which have the power to change everyone who reads them.” – Elena Kostiukovici

The Train to Samarkand is an emotional novel written by the talented Russian author Guzel Yakhina. If you’ve already read her renowned Zuleikha, then you’re likely captivated by the storytelling prowess that, once again, transports you into a harsh and brutally challenging period of history. This is a book that invites deep reflection on history and the lessons it offers, urging us not to repeat past mistakes.

Historical context

The story unfolds in 1923, following the end of the Russian Revolution and Civil War. These were years marked by instability in every aspect of life. The policy of requisitioning brought devastation, leading to the deaths of millions. Many children were left orphaned, wandering alone or in groups, starving and aimless.

In response, the Soviet government initiated a project to address the issue of homelessness, transporting orphaned or abandoned children by train to the south, where living conditions were more favorable. In this novel, one such special train, nicknamed the garland, carries hundreds of orphans from Kazan to Samarkand in an effort to save them from starvation—and not just starvation, but also disease, cold, and countless other deprivations. Essential supplies for basic survival were nearly nonexistent. This grueling mission is led by the stern children’s commissar Belaia and the youth forces combatant Deev, accompanied by other well-meaning but unqualified individuals. But in the end, what diplomas does one need for survival?

“Yes, right now. Yes, that’s how it is: everything that happened to you—whether recently or long ago, in any year of your life—never vanishes without a trace. It happens again, today, tomorrow, always.”

What might seem like a unique experience—and in many ways it is—carries a universal quality through the questions it raises. As a reader, you often wonder if there could have been other solutions in the face of such adversity. How does one choose solutions to life-or-death problems when everything necessary for survival is utterly absent? Do they dare to believe in a different world from which to draw what’s missing, or do they surrender, convinced that their world is the only one that exists? This train symbolizes survival, and the journey becomes a choreography where hope and despair alternate so swiftly that at times, it’s nearly impossible to tell them apart.

A Different Ark, A Different Noah

“The children were now his strength and wealth, his knowledge and fortune, his protectors. In the Turkestan desert, it was not Deev saving the children, but the children saving Deev.”

As the author suggests, the garland is a kind of ark, not filled with animals, but with children. And the Noah figure, Deev, is a seemingly simple man whose tough life experiences have transformed him into a savior. He might not be able to do much for himself, but he’s willing to do anything for these children, who, in turn, become his saviors. His psychological scars shape his approach to the mission and his relationships with others. To achieve his goal, he’s ready to make sacrifices, even putting his own life at risk, making this journey one of redemption for him.

“Belaia is so principled and heartless that you simply can’t get along with her; she’s not a person, but a stone…”

Commissar Belaia is portrayed as a rigid and cold character, but her steadfastness during the journey isn’t merely driven by extreme conscientiousness; it stems from the harsh lessons life has taught her. She’s learned that “being good doesn’t mean promising the impossible, sighing, or shedding tears for the poor sick souls… Being good means thinking of everything. Fearing everything. And preventing everything. To be good, you have to know how. You have to know how to say no. How to control. How to punish…”

The children in the garland, now belonging to no one, with souls scorched by trauma, vividly depict the horrors and emptiness that war leaves behind. The trials they’ve endured and the losses they’ve suffered cannot be justified by national ideals, political motivations, or economic reasons. The author skillfully highlights the devastating effects of famine, illustrating how it altered the children’s lives, mentalities, and even the way they communicated.

A Novel About Humanity

The Train to Samarkand is a powerful novel, where Guzel Yakhina’s mastery perfectly captures landscapes, objects, and bodies with a photographic precision while evoking deep empathy for these children with tormented souls and bodies. The sympathy for both, the children and the caretakers of the garland, plants a resolute question in your mind: How can I help? Perhaps this is the author’s greatest achievement: the ability to rekindle our sense of humanity.