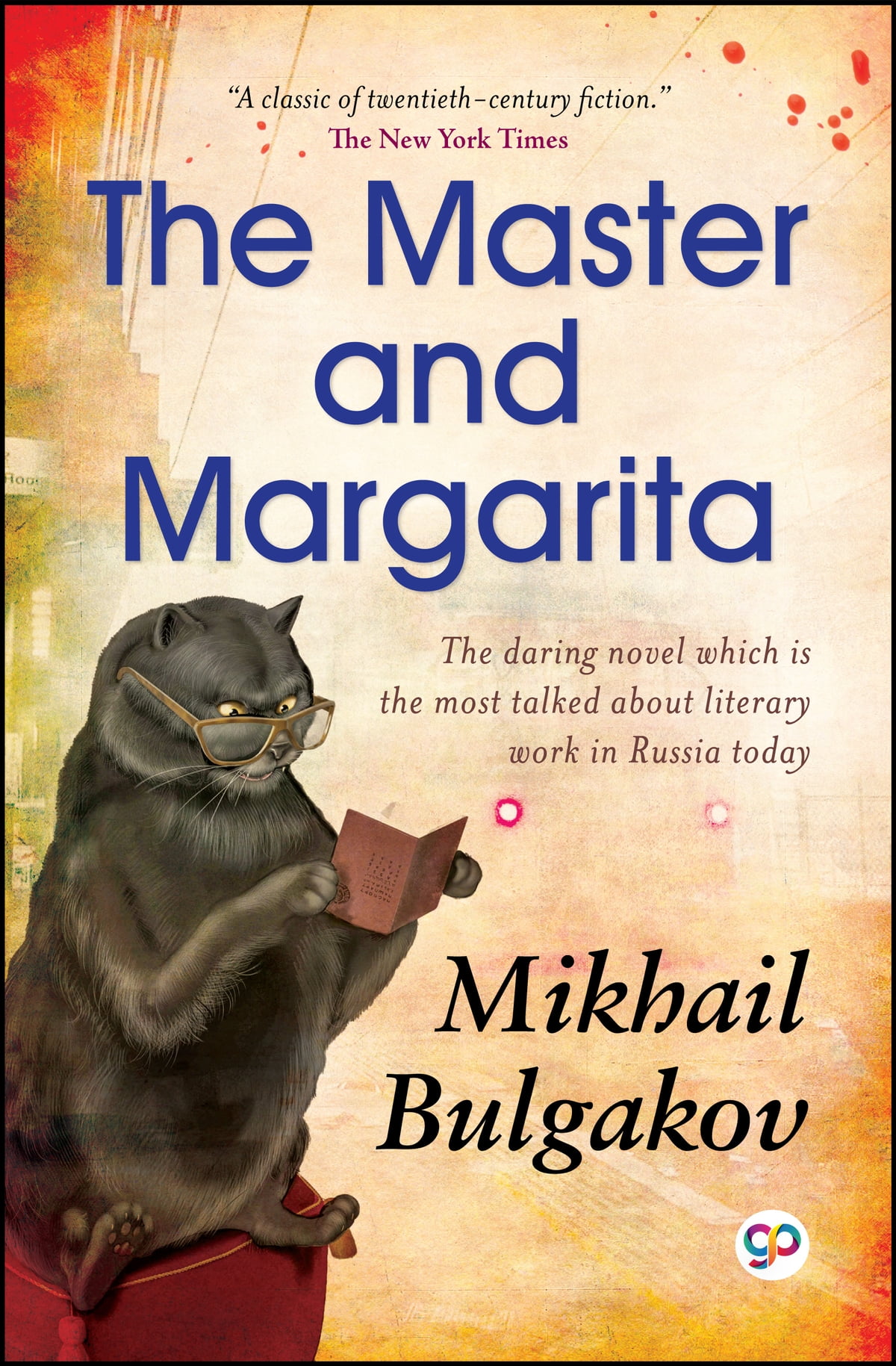

MY REVIEW OF A TIMELESS CLASSIC

The Master and Margarita

Bulgakov‘s masterpiece. A captivating blend of love, madness, and the supernatural in Stalinist Moscow. A timeless literary gem. But is this book actually worth your time?

“The Master and Margarita is a wild, imaginative, and brilliant story, but it is also a novel of ideas, where the themes of good and evil, innocence and guilt, freedom and oppression swirl in a suspenseful tale about a writer’s Faustian pact.” – New York Times

The Master and Margarita is one of the most acclaimed novels of the 20th century and the best-known work of Mikhail Bulgakov. A gem of modern classical literature, the novel portrays the Moscow society of the 1930s, a society corroded by communism under Stalin’s dictatorship. Bulgakov‘s critical tone was so strong in this work that it was first published more than 20 years after his death. His criticism targeted both the ruling system and certain religious aspects. Its cultural impact is lasting, as the author explores not only Moscow society at that time but also philosophical and existential questions that are still relevant today.

By framing human cowardice as the gravest vice, the theme of a pact with the devil seems inevitable in a work that explores the human spirit, love, and the confrontation between good and evil. Thus, by masterfully reinterpreting the Faustian myth, using magical realism and satire, Bulgakov effectively reflects the moral aspects of the society of his time.

Good and Evil Together

The story begins with a meeting between Berlioz, the editor-in-chief of a literary-artistic magazine and president of the literary group called MASSOLIT, and his discussion partner, Ivan Nikolaevich Ponyrev, a writer who publishes under the pseudonym Bezdomny. The latter was asked to write an anti-religious poem for the aforementioned magazine, and Berlioz, a staunch atheist, explains that the poem is a mistake because, even though it depicts a flawed Jesus, it portrays a person who actually existed, which is false from Berlioz‘s point of view. However, their conversation is interrupted by Professor Woland. Woland, none other than Satan himself, enters the novel by arguing for the existence of Jesus, claiming that he even witnessed Pontius Pilate approving his crucifixion. In the same conversation, Woland also informs Berlioz of how he would soon die: decapitated. Woland‘s prophecy comes true, and Berlioz loses his head under a tram, just as predicted. This marks the beginning of a festival of madness, orchestrated by a supposed hypnosis. Woland has a team as efficient as it is malevolent, consisting of Koroviev, who always wore pince-nez with cracked lenses, Azazello with one fang protruding from his mouth, and Behemoth, a talking cat. The other thread of the novel revolves around the moment of Yeshua’s death sentence under the authority of Roman governor Pontius Pilate. Yeshua’s compassionate view of humanity creates internal conflict for Pilate, who tries to offer the crowd alternatives that could spare the condemned man, but without success.

In the chapter titled Ivan’s Duplication, the much-anticipated Master finally appears. His love story with Margarita begins at a time when she is unhappy in her marriage, but their relationship flows, unrestricted by norms, transcending any boundaries of the mind, seeking fulfillment in places that would not typically offer solutions for lovers. At the time of their meeting, the Master was completely disillusioned, isolated, and in great suffering. Margarita desires so much to bring him back to life that she is willing to make a pact with the devil to do so…

Woland is the embodiment of evil, Satan himself, but his role, paradoxically, is to identify human wickedness, expose it, and punish it. Thus, he acts more like a supreme judge who condemns the lack of morality in Moscow society. This clarity in addressing the religious dimension of evil invites us to a profound reflection: does human wickedness originate from hell, or is it simply a manifestation specific to human nature, which, when amplified and acted upon with varying degrees of consequences, leads the soul to the dark depths of Hell to be punished for eternity? This exposition challenges us to reevaluate not only the source of evil but also our responsibility in perpetuating or annihilating it.

Cowardice Through History

Cowardice "Then"

“Cowardice is undoubtedly one of the most terrible vices,” said Yeshua Ha-Nozri. “No, philosopher, I disagree with you: it is the most terrible of vices.”

The role of free will becomes crucial, and cowardice, the ultimate sin, brings devastating consequences not only for the individual but also for those involved, sometimes changing the course of history. In this sense, we have the example of Pilate, who embodies the moral dilemma: will he muster the courage to defend the life of an innocent person, or will he resign, afraid of losing the privileges his position offers if he opposes the crowd? As we all know, the biblical character acted cowardly, subjecting his conscience to constant torment as a result of abandoning his principles and moral values, leading to the death of an innocent man. For Bulgakov, cowardice is not just a personal failure but the abandonment of humanity itself. Pilate‘s inner turmoil after his decision reflects the author’s view: cowardice is never a compromise that can offer a solution, not even a temporary one. It is an act of betrayal of oneself, which is paid for with an unstoppable inner torment, a hellish anguish where the conscience becomes one’s own hell.

Cowardice "Now"

As mentioned, Russian society in the 1930s was suffering under Stalinist dictatorship. Thus, Bulgakov’s Moscow is a place of hypocrisy and compromise, with a strong scent of fear. People, frightened, are unable to muster the courage to express their convictions and oppose the injustices to which they are subjected. This generalized fear prevents the annihilation of evil and the change of power, making cowardice a collective sin that condemns the entire society to suffering. Cowardice is perpetuated through conformity and silence, generated, of course, by fear.

Amidst these compromises, the Master and Margarita live, capable of entering extreme situations to defend their love, in which they believe more than anything; two exceptions, as they are able, in the midst of danger, to live their lives authentically without giving up their values.

A Timeless Novel

The Master and Margarita is the type of novel to which one can return time and again, as its countless characters and actions, symbolism, complexity, and depth of the themes require attention and importance, even from a well-trained mind. Each rereading offers the chance to rediscover a new experience or perspective, which can provide the reader today with greater clarity about their own identity and who they aspire to become.